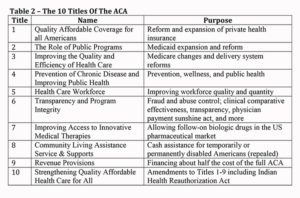

In 2010, Congress passed, and the President signed, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. This law runs roughly 1000 pages in length and features 10 Titles or chapters as described below:

Economist Jonathan Gruber, a chief architect of both the Massachusetts reform in 2006 and the ACA, argues that the act stands on a three legged stool; therefore, the following three components are necessary for the program to succeed in reaching its primary goal: a significant reduction in the share of the population without health insurance.

- Private insurance market reform based on no pre-existing condition exclusions and adjusted community rating

- Mandated purchase by individuals and businesses

- Subsidized purchase inversely related to income or through expanded Medicaid.

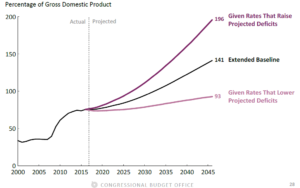

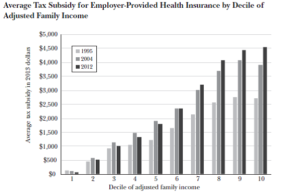

Subsidies for the purchase of health insurance for people under 65 have been in existence since the 1950s. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that for 2016, the net amount of Federal subsidies for those under age 65 will be $660 billion, over 20 percent of what is spent annually on medical care in the U.S. Of these, the ACA accounts for roughly $82 billion and employer-based coverage $268 billion, with the latter amount regressively structured as displayed in the following graphic.

Despite these efforts, the burden of health expenditures has continued to rise for American workers and their families. Since 2011, worker earnings have risen by 11%, while premiums have gone up by 19%. Furthermore, the relatively small rise in premiums over the past five years reflects the increased share of costs passed on to workers through a 63% increase in the average deductible portion of their insurance package; that is, the amount people must spend, with some exceptions for preventive service and primary care, before expenses are covered by insurance.

The ACA has been effective in reducing the number of uninsured from roughly 50 million to 30 million with about 12 million purchasing insurance on the newly created market exchanges for individual insurance and 8 million through expanded Medicaid in 31 states (and the District of Columbia.) In particular, those with incomes below 200% of the Federal Poverty Level have seen their rate of uninsurance fall by more than 10 percentage points. Furthermore, quality improvement initiatives have been effective in reducing the rate of patient harm in hospitals by 17% for both 2013 and 2014.

The individual market exchanges, however, have not achieved the stability required for sustainable existence. Recent premiums have risen markedly, although increased premium subsidies based on income, have moderated the effects for lower middle income participants. Three components of the program designed to assist in stabilizing these exchanges in its first three years – risk adjustment, re-insurance, and risk corridors – have been inadequately funded to sustain the participation of many private insurance companies. Several insurers have dropped out of the exchanges as well as sued the Federal government for payments they expected to receive through the risk corridor program (which is set to expire at the end of 2016.) Additionally, the penalties for lack of purchase of insurance have been inadequate to induce relatively young and healthy Americans to enroll; thus, the existent risk pools in the market exchanges tend to consist of those in relatively poor health and low income.

In short, even without a significant change in Federal administration, major reform or at least major gap filling would be required to sustain the market exchange portion of the ACA. Of course, the recently elected President and the majorities in Congress have loudly proclaimed their intent to “repeal and replace” Obamacare. What should we expect?

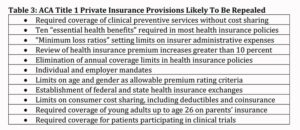

There is much speculation about what the new President and Congress will do. They will NOT be able to repeal the entire act as that would require 60 votes in the Senate, which will not happen given that no Democrat is likely to vote for repeal. Much of the existent Republican proposals focus on repealing the provisions that relate to private insurance (Title 1 of the Act.)

The “A Better Way” Plan proposed by Congressmen Tom Price, M.D. (newly selected to head the Department of Health and Human Services) and Paul Ryan (Speaker of the House) highlights several key provisions including (but not limited to)

The “A Better Way” Plan proposed by Congressmen Tom Price, M.D. (newly selected to head the Department of Health and Human Services) and Paul Ryan (Speaker of the House) highlights several key provisions including (but not limited to)

- Providing refundable tax credits for those without employer sponsored health plans

- Capping the tax breaks available to those who receive employer organized coverage

- Allowing people to purchase insurance offered in other states beside the ones in which they live

- Encouraging coalitions of individuals and businesses to jointly purchase insurance

- Guaranteeing coverage of people who maintain continuous insurance (i.e., no pre-existing conditions clauses)

- Allowing children to remain on their parents’ plan until they reach the age of 26

- Turning Medicaid in to a Federal block grant program with minimal Federal mandates

- Strengthening Medicare Advantage with premium support as a way to control the cost of medical services to the elderly

As one can readily tell, the “A Better Way” proposal shares many of the objectives with the proponents of the Affordable Care Act. In a previous blog posting, I address to what degree Republicans and Democrats share goals and means. Skilled leaders who seek to act in the public interest would be able to find a viable path to sustainable health policy reform. This scarce commodity, however, is likely to be absent from the forthcoming debate about how best to reform our very inefficient and inequitable structure, some call the U.S. health care system.

For a more complete discussion of the above topics, see the slides for my presentation entitled “The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare); an Efficient and Equitable Path to Life Liberty, and the Pursuit of Health?” PPACA – Noon Hour Philosophers -Nov 2016