The Deadliest Virus Ever Known and the US Innovation System

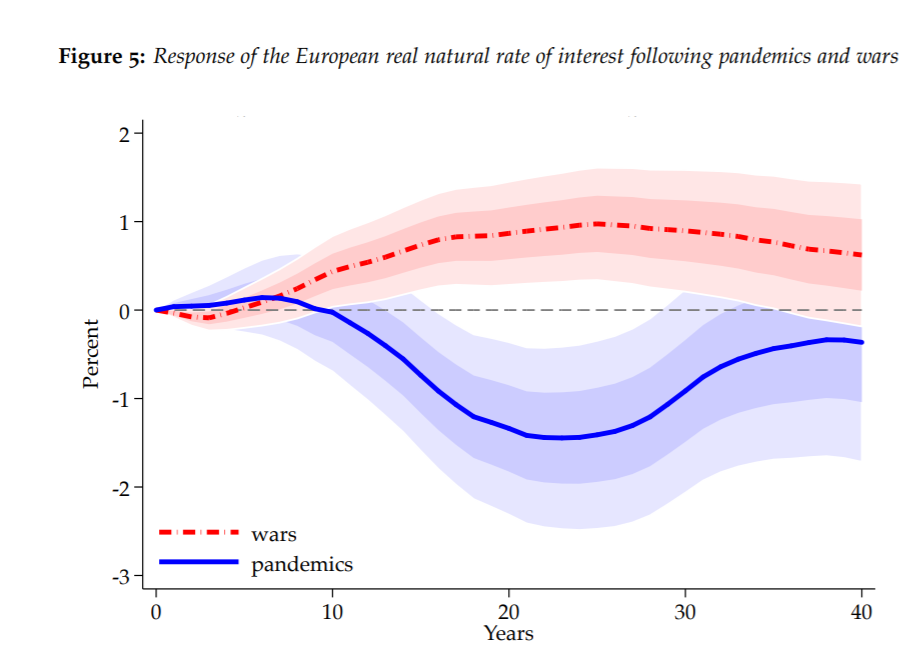

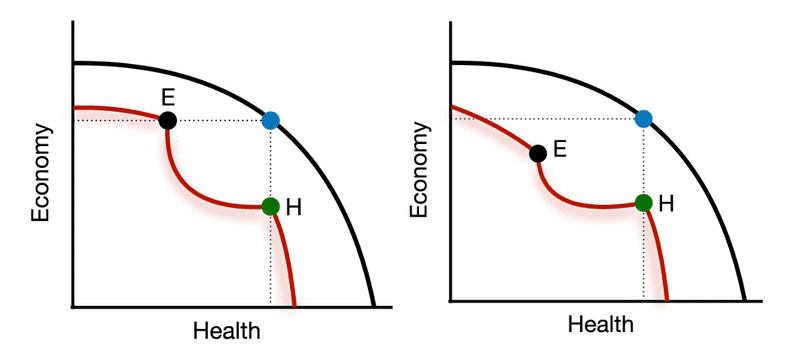

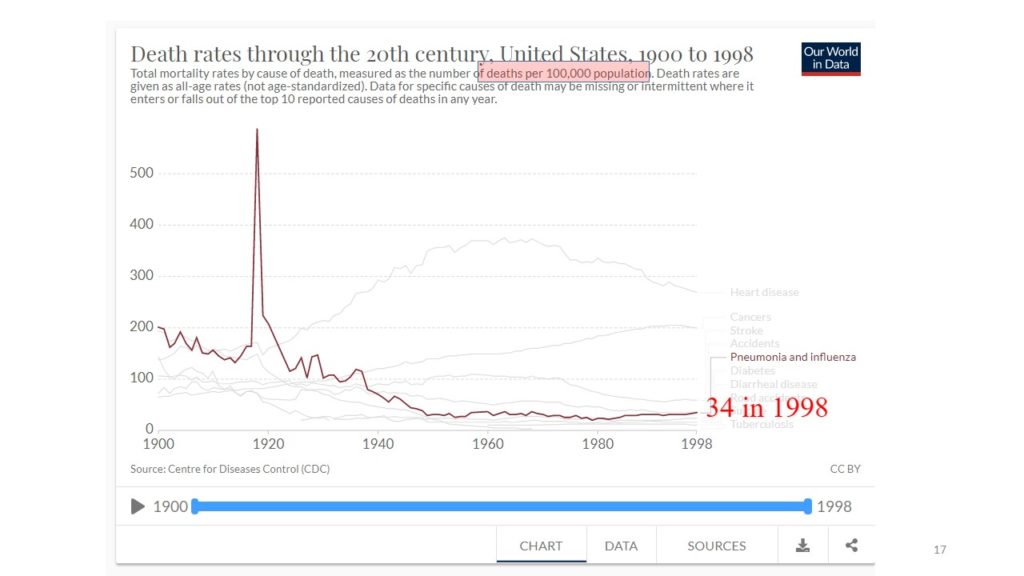

The two main topics this week are quite expansive, so we will just weak our proverbial beaks. The first is the great influenza epidemic of 1918, which you have undoubtedly heard about. The Gladwell article is fascinating and Garrett provides us with a glimpse of the economic research. There are a number of excellent papers that use this event to study the effects of “non-pharmaceutical interventions,” the macro economic effects of pandemics, the exacerbating effects of air pollution on mortality rates, and the like.

The second main topic is innovation and public policy, which is essentially a course in and of itself. The Gans book seems to be as good of a starting point as any, and you can go from that to looking at the prospects for a CoVID-19 vaccination.

The “Flu”

- Malcolm Gladwell, “The Deadliest Virus Ever Known.” The New Yorker. September 29, 1997.

- Garrett, Thomas A. “Pandemic economics: The 1918 influenza and its modern-day implications.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 90.March/April 2008 (2008).

Two Videos on Innovation from Marginal Revolution University

- “The Economics of Ideas,”

- “Patents, Prizes, Subsidies“

- Joshua Gans, “Rallying Innovation,” Chapter 7 of Economics in the Age of CoVID-19, MIT Press

Vaccines

- Ewen Callaway, E. “The race for coronavirus vaccines: a graphical guide.” Nature 580.7805 (2020): 576.

- Roxanne Khamsi, “Can the World Make Enough Coronavirus Vaccine?” Nature (2020).

- “Can the world find a good covid-19 vaccine quickly enough?” The Economist, April 16, 2020

Student Presentations

More on the 1918 Flu

- Robert J. Barro, José F. Ursúa, and Joanna Weng. “The coronavirus and the great influenza pandemic: Lessons from the “Spanish flu” for the coronavirus’s potential effects on mortality and economic activity,” w26866. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020.

- Robert J. Barro, “Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions and Mortality in U.S. Cities during the Great Influenza Pandemic, 1918-1919,” w27049 National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020.

- Elizabeth Brainerd and Mark V. Siegler. “The economic effects of the 1918 influenza epidemic.” Mimeo. (2003).

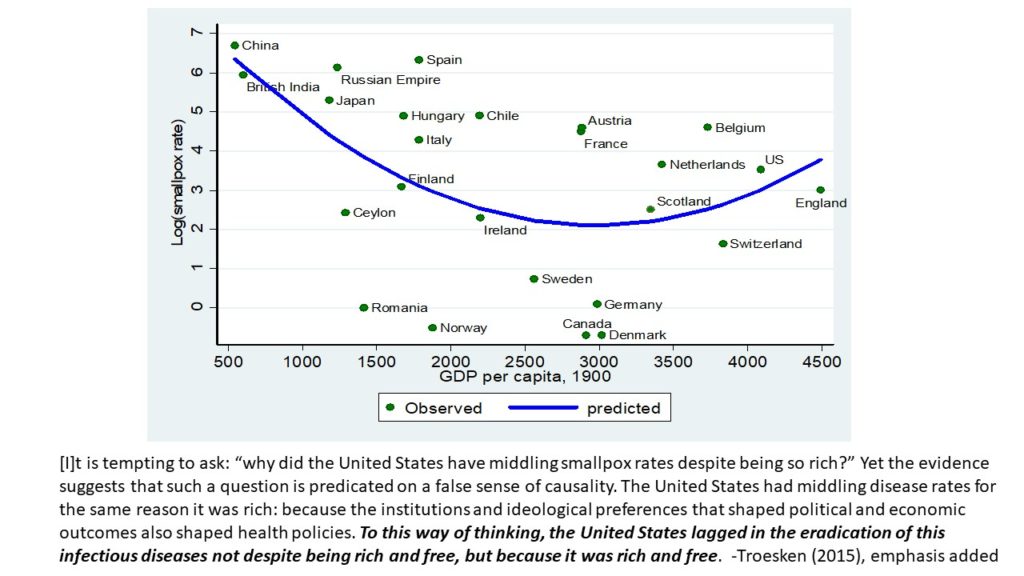

- Karen Clay & Joshua Lewis & Edson Severnini, 2018. “Pollution, Infectious Disease, and Mortality: Evidence from the 1918 Spanish Influenza Pandemic,” The Journal of Economic History, vol 78(04), pages 1179-1209

Congressional Dominance?

- Matt E. Ryan “Allocating infection: The political economy of the Swine Flu (H1N1) vaccine.” Economic Inquiry 52.1 (2014): 138-154.

The Flu Today

- Sara Markowitz, Erik Nesson, and Joshua J. Robinson. “The effects of employment on influenza rates.” Economics & Human Biology 34 (2019): 286-295.

- Chalres Stoecker, Charles, Nicholas J. Sanders, and Alan Barreca. “Success Is something to sneeze at: Influenza mortality in cities that participate in the Super Bowl.” American Journal of Health Economics 2.1 (2016): 125-143.

- Steve Cicala et al. “Expected Health Effects of Reduced Air Pollution from COVID-19 Social Distancing.” University of Chicago Becker-Friedman Institute Working Paper. (2020).

Misc

- Austin Wright et al. “Poverty and economic dislocation reduce compliance with covid-19 shelter-in-place protocols.” University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper 2020-40 (2020).